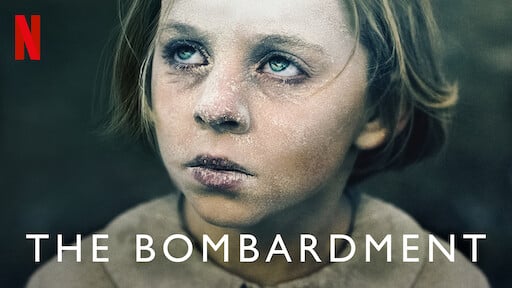

The Danish-original period piece war drama ‘The Bombardment,’ directed by Ole Bornedal of ‘Nightwatch‘ renown, produces a shock by showing the visceral spectacle of destruction through the eyes of children.

Henry is tense from the start, as he witnesses three girls die in front of his eyes. Henry is unable to communicate as a result of his shock, yet his life continues to move forward despite the uncertainty.

Henry goes cake hunting with Rigmor and Eva’s help. In times of crisis, however, weather may change quickly, and an unanticipated bombardment reveals a vision of the apocalypse in a catholic church and school.

Many familiar figures from the Danish film industry appear in the enervating drama, from Alex Hogh Andersen to Susse Wold.

You could ask how much of the storey is based on historical events. Let us delve deeper into the concept if it has occurred to you.

Must Read: ‘The Bombardment’ (2022) Recap And Ending Explained

Is ‘The Bombardment’ Movie Based on True Story?

Yes, the tale behind ‘The Bombardment‘ is accurate. In recent months, Netflix has seen an influx of war films, with titles like ‘The Forgotten Battle‘ and the critically praised ‘Eye In The Sky’ joining its ever-growing catalogue of film titles.

Ole Bornedal directed the film from his own script, which was based on a little-known World War II episode.

As a result, the picture reads like a significant blip in humanity’s history. It covers difficult topics like God’s existence and man’s mistakes.

The storey begins in Copenhagen in 1945, when Europe was still reeling from World War II. In comparison to cities like Berlin and Rome, Copenhagen saw less heat during the war.

The city was quickly taken over by the Germans. In April 1940, German aircraft dropped ‘OPROP!’ leaflets from the skies. The Danish military recognised their weakness in the face of the Third Reich and surrendered to the Nazi soldiers.

The Germans had bombs on standby in case they needed them, but they were able to conquer the city with minimal damage.

They turned Copenhagen into an operations centre, relocating the Gestapo headquarters to Aarhus (dubbed “the Shell House” by locals).

The war was intensifying, and Nazi Germany was threatening the continent’s existence as well as its unique cultures. As tensions rose, Ole Lippmann and other members of the Danish resistance secretly contacted with the British, who dispatched 20 Royal Air Force Mosquitoes to devastate the Gestapo headquarters.

In the meantime, the Germans kidnapped members of the Danish resistance. They used the resistance members as human shields beneath the building’s roof.

The Royal Air Force devised a strategy to strike sideways, with the primary goal of destroying Gestapo archives containing crucial information on the resistance.

The RAF launched the attack on March 21, 1945, under the codename “Operation Carthage.” Unfortunately, one of the fighter jets from the initial wave collided with a lamppost and crashed into a garage near a catholic school.

Two of the second wave’s jets mistook the fire from the crash for their objective and dropped bombs on the Institut Jeanne d’Arc, a catholic school.

The school, also known as Den Franske Skole, was founded in 1924 by the Sisters of St. Joseph, with the architecture constructed by Danish architect Christian Mandrup-Poulsen.

They had also built the Institut Sankt Joseph in the city’s Osterbro neighbourhood prior to this institution.

The horrific bombing event resulted in the deaths of a large number of individuals, almost all of whom were civilians, and the majority of whom were children.

There were no bombing warnings issued. As a result, the deceased were unable to reach the protection of the underground bunker.

86 children and 16 adults were killed, with 67 children and 35 adults suffering serious injuries. The tragedy sent shockwaves across the city. Locals flocked to the streets to assist with the rescue effort.

They included children like Rigmor and Jenny, as well as nuns like Teresa. The remaining buildings were demolished in the aftermath of the bombing, and the surviving students were transferred to Institut Sankt Joseph.

Six apartment structures now stand on the property. The government commissioned sculptor Max Anderson to create a monument on the site in 1953, and it still stands today.

When all factors are considered, the movie closely resembles what occurred on the ground. Some of the characters, though, could be made up.